Urban/Rural divide in Colorado

The urban/rural divide in American politics has roots that extend back to the founding of the country. From the first history courses students take in the U.S., we learn about the different interests of the more agrarian regions of the country and the more urban parts and how those differences shaped the early history of the country. Today, we still see substantial differences between more urban and more rural places.

Politics in Colorado can be understood partially through the lens of urban/rural conflict. This post will discuss how urban and rural dynamics plays out in the Colorado political landscape.

The surprisingly difficult job of defining urban and rural places

It is surprisingly difficult to come up with a way to objectively classify places as “urban” or “rural” (and these problems are only compounded when trying to classify an area as “suburban” or “exurban”). For many of us, Justice Potter’s “I know it when I see it” test (applied in somewhat different circumstances) suffices, but when one is in the business of quantifying things lines inevitably need to be drawn.

One option is to ask people to self-identify as living in an urban, suburban or rural place. As I have written elsewhere, self-reports of urbanicity seem to have a fair amount of subjectivity, and we see a disagreement between people who live in very similar circumstances when it comes to describing their communities. I am certainly not saying that these self-reports from survey respondents are not valid, but in the absence of survey data and to provide a consistent, objective measure, we have to turn to other sources.

Development intensity

One promising way to look at this (at least over the past 40 years or so) is to turn to the National Land Cover Database. The NLCD is produced and maintained by the U.S. Geologic Survey, and it transforms forty years of satellite imagery into quantitative measurements of land cover. The dataset classifies each 30-meter square portion of the country into one of a range of categories. For the purposes of this post, I focus on their development classifications. They produce four categories of development intensity (open space, low, medium, and high intensity).

The animation below shows the development of the Northern Front Range since 1985 to give a sense of what the raw data looks like. I also make extensive use of this data source in my fact sheets.

Change in development in Northern Colorado, 1985-2024

As the graphic shows, this area of Colorado has grown rapidly over the past 40 years. Colorado's total population has grown by more than 50% between 1990 and today. The rate of growth in the Colorado is among the fastest in the country. This population growth has also changed the urban/rural balance in the state.

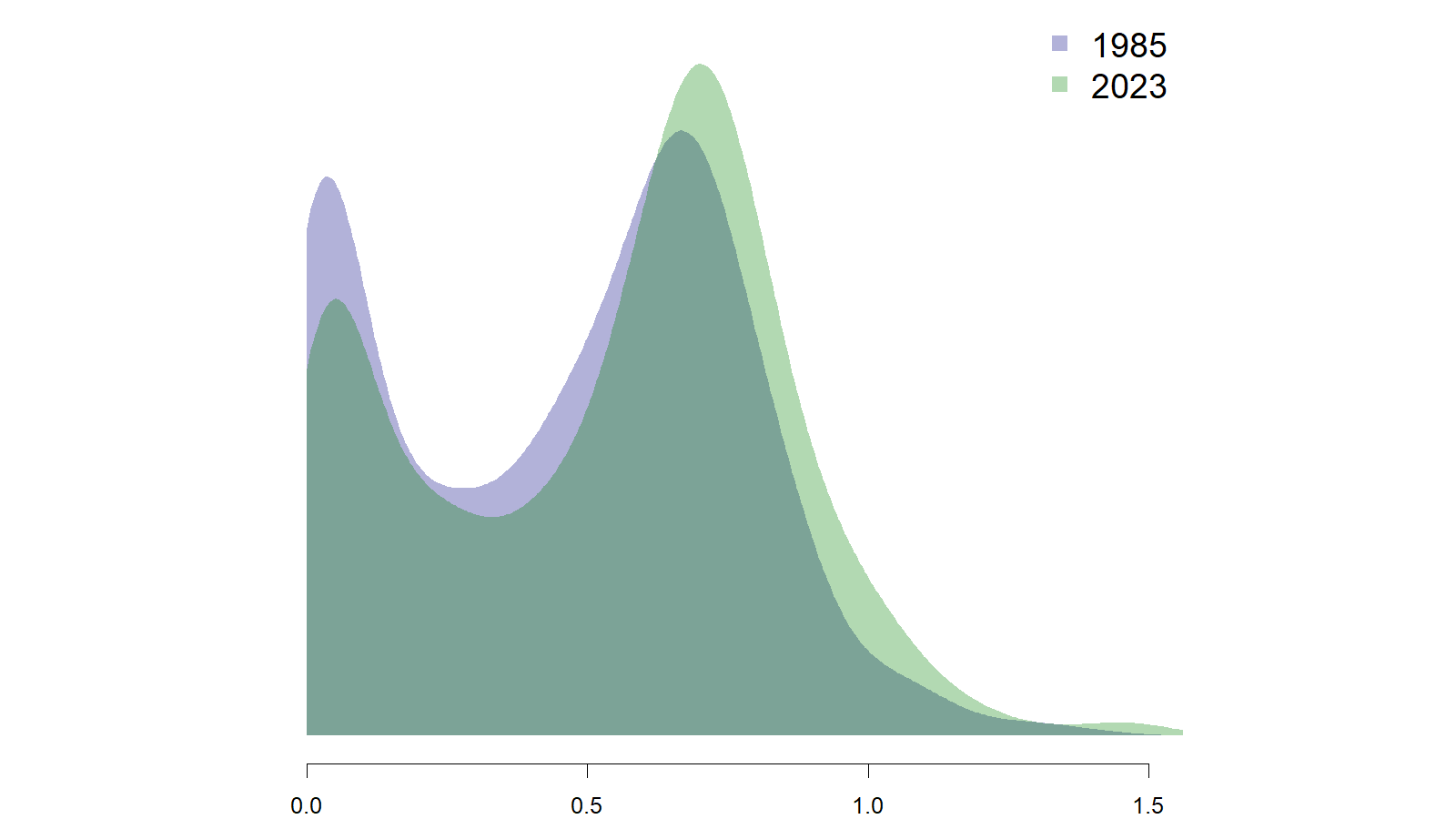

Change in the distribution of development in Colorado, 1985 and 2024

In 1985, over 40% of the state's population lived in very low development areas (areas that scored less than 0.2 in the graphic above). Today, that share has dropped to about a quarter. In 1985, less than 10% of the state's population lived in places with very high levels of development (greater than 0.8 in the graphic above). Today, that share has more than doubled to over one-in-five.

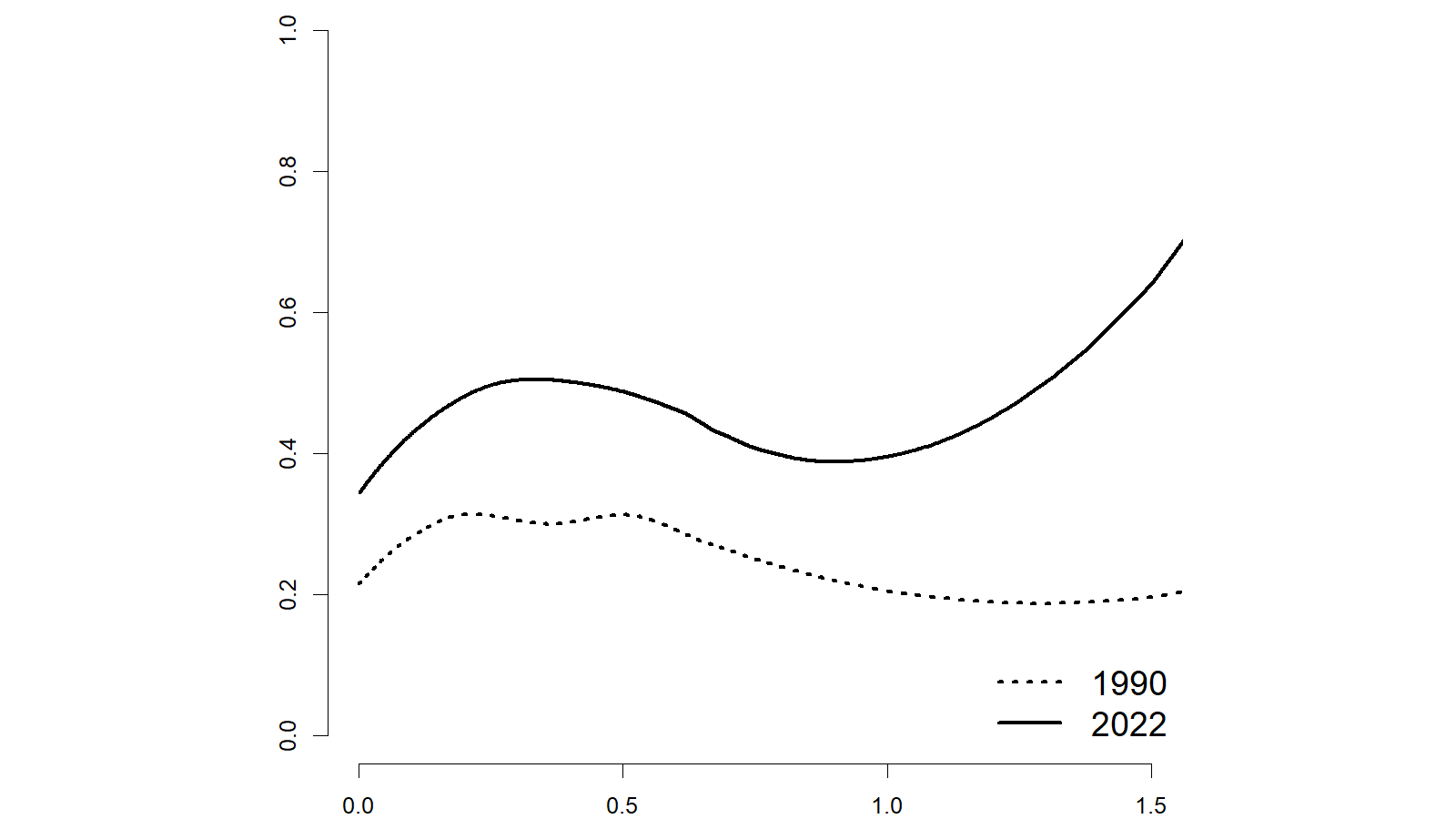

In a previous post, I looked at the dynamics of educational attainment in Colorado. The plot below shows the average share of the Colorado population with a college degree across different levels of development.

Development intensity and educational attainment in Colorado, 1990 and 2022

When interpreting this graphic, it is important to remember that the largest part of the population (as shown in the density plot above), lives in areas that are scored less than 0.8 on the development scale. The lowest development parts of the state have somewhat lower levels of college graduates in both 1990 and today. Educational attainment is somewhat higher on average in the medium development parts of the state. The big upswing among among the highest development places seems to be new, but bear in mind that there are not many places in Colorado that score higher than 1 on the development score.

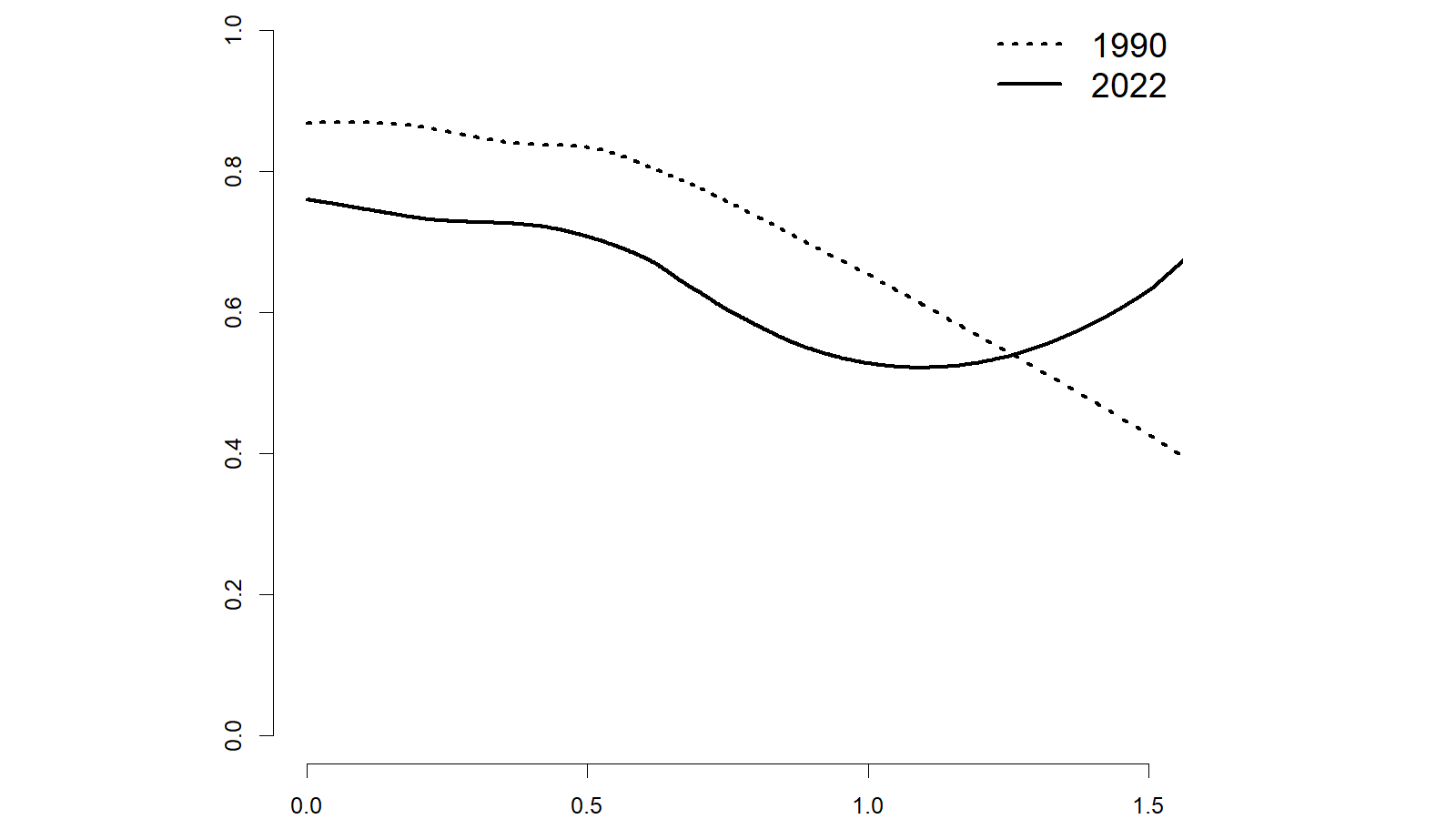

The graphic below shows the relationship between urbanicity and racial and ethnic composition in Colorado. In 1990, the relationship is fairly linear. The more developed a neighborhood, the lower the share of non-Hispanic White people living in that place. The relationship today looks much the same, until we get to the places with the highest levels of development. The (few) neighborhoods that are in the highest development parts of the state are less diverse on average today than similarly developed places were 30 years ago.

Development intensity and racial and ethnic population in Colorado, 1990 and 2022

Political divides by urbanicity in Colorado

In the 2024 election, Pew Research Center found a large divide among voters by their community type. Among voters who described their communities as rural, 69% voted for Trump compared to just 29% supporting Harris, and the pattern is nearly completely reversed among voters who said they live in urban communities (65% voted for Harris; 33% for Trump). A similar pattern holds in Colorado.

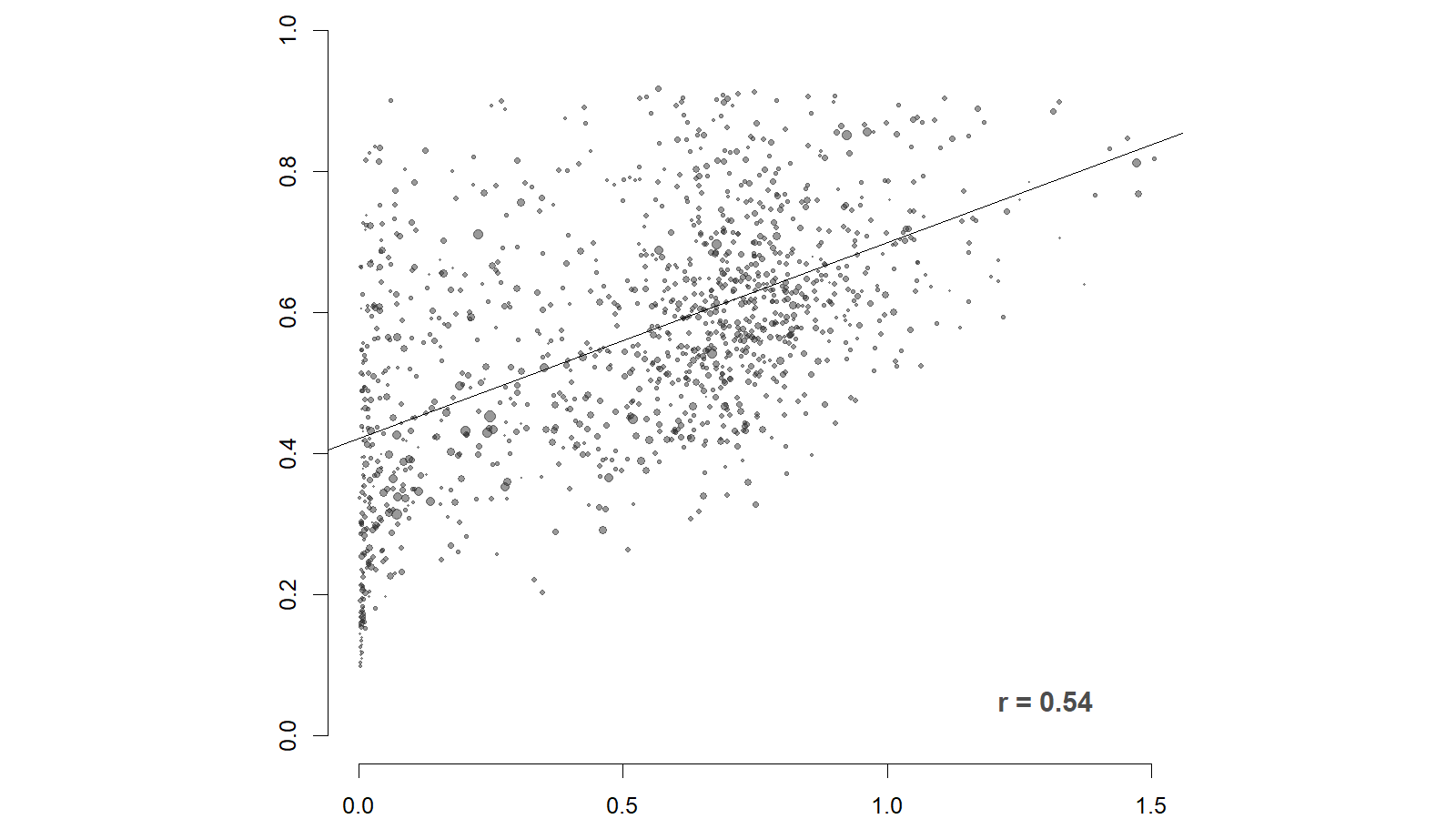

Democratic voting by urbanicity in Colorado, 2024

Concluding thoughts

This post has focused on describing how more and less urban places are different from one another in Colorado, but it does not (and cannot) answer the nagging question of why these differences persist. As with many social science questions, causation is very difficult to prove. Survey data from Pew Research Center shows that there is a large partisan divide in community preferences. The Pew analysis showed that 72% of Republicans compared to just 43% of Democrats said that they would prefer living in a home that was bigger and further apart from other homes even if it meant it was located several miles away from schools and shops when given the option between that and a smaller home in a more walkable place. It is plausible that one driver of the differences is simply selection into places that best suit their lifestyle (for example, this reporting by NPR).

It is also plausible that people's answers to questions like the community preference item referenced above are, at least in part, informed by their current circumstances, and there are many considerations that go into relocation decisions. Most of us who move from one community to another do not have the luxury (or even the desire) to select primarily based on political considerations.

The data discussed above also reveals that the dynamics of place can change over time. For example, we saw that the racial and ethnic composition of the must heavily developed places in Colorado has shifted over the past 30 years. In 1990, the most developed places in the state were also the most diverse, while today places with similar levels of development are actually less diverse than they were 30 years ago despite the overall changes to the state's demographics.